When doing a research project in ELT teacher training programmes, many students evaluate various language learning materials, such as textbooks or other resources. This is fairly standard and uncontroversial practice, but it is always useful to be familiar with the legal and ethical implications associated with such research. In fact, a student recently asked me whether evaluating an EFL textbook without the authors’ permission was even legal, and I would like to share my response, in case it is of some use to others as well.

The student’s question

Could someone give me an answer to a question of legal nature about my research for a dissertation (masters course)? I am going to review EFL textbooks (upper intermediate / advanced level) in the light of the global education & critical thinking.

Do I need to ask written permission from the publishers? I have tried to read what the law is but I am not sure I feel confident in interpreting the law. Is my research within “fair dealing”?

I am going to do a quantitative analysis, to check the visibility of the global issues & the amount of exercises developing critical thinking skills and then a qualitative analysis within the framework of global education. What do you advise me to do? Thanks!

What does the law say about evaluating textbooks?

I believe that the applicable law should be the law of the land where one writes their thesis. In almost all cases, freedom of speech and freedom of research activity are fundamental rights, and would take precedence over any legal concerns a publisher might raise.

Simply put, one should be able to use whatever data you have legally obtained without problems. If one legally owns a book, or has aquired it lawfully (e.g. by borrowing it from a library), one should have the right to use it in any almost1 way that they see fit. This includes mining it for data, reflecting on the data and sharing one’s informed opinion about the book.

So, you don’t need a written permission to evaluate a book.

Writing about your findings

That said, one still needs to be careful about how one reports on the findings when evaluating a textbook, so that copyright law does not come into effect.

On the principle that it is best to err on the side of caution, one should in generally avoid reproducing material, such as images or extensive text, from the coursebooks in one’s dissertation. One the other hand, small snippets that are essential for developing ones argument, likely fall under ‘fair use’ or similar provisions that exempt them from copyright restrictions.

In ascertaining whether something is ‘fair use’ one would need to consider at least three factors.

How long is the extract?

Fair use gives one the right to reproduce any extracts that are necessary to make a point, but nothing longer than that. This is difficult to quantify in absolute terms, but common sense does apply. You shouldn’t reporduce an entire page just so present a reading passage, and you needn’t copy an entire exercise if one or two examples are enough to help readers understand what it is all about.

How necessary is the extract?

Sometimes you just can’t make a point without grounding it on specific examples. It is also easier to show a figure rather than describe it. One might also make the argument that presenting the actual textbook content allows readers to draw their own conclusions, rather than rely on the reseracher’s interpretation. In all these, and similar, cases using textbook content would be fair use.

What effect does the reproduction have on the value of the textbook?

Let’s take a hypothetical example: Suppose a student were to reporduce an entire texbook unit in the appendix of a term paper, which ends up in an institutional repository. And let us also suppose that several other students did the same thing with other units of the same textbook. Then, one could theoretically reconstruct the book from material available online. A publisher might then make a reasonable argument that such a practice damages their commercial interests.

To avoid this, it may be a good idea to use low resolution pictures, or stamp ‘Sample’ on them. This would ensure that one has taken all reasonable precautions balance the right to research and the rights the publisher enjoys under copyright law.

When reproducing copyrighted content, consider the questions: (a) is it too much? (b) is it really necessary? (c) is it commercially useful?

I hope that you found this text useful; if you have other questions about conducting an ELT research project, why don’t you drop a line in the contents or by using the contact form? Also feel very free to share this post with anyone who might find it useful.

Notes

- An obvious exception of this would be unauthorised copying. However this is a limited exception, and that is why the publishers are usually required to print this information on the book itself. ↩︎

About me

I am an applied linguist and language teacher educator at the University of Thessaly in Greece. I have published extensively on ELT/TESOL and langauge teacher research. Over the years, I have supervised multiple student research projects. If you would like read more about my research supervision activity, please visit this page.

About this post

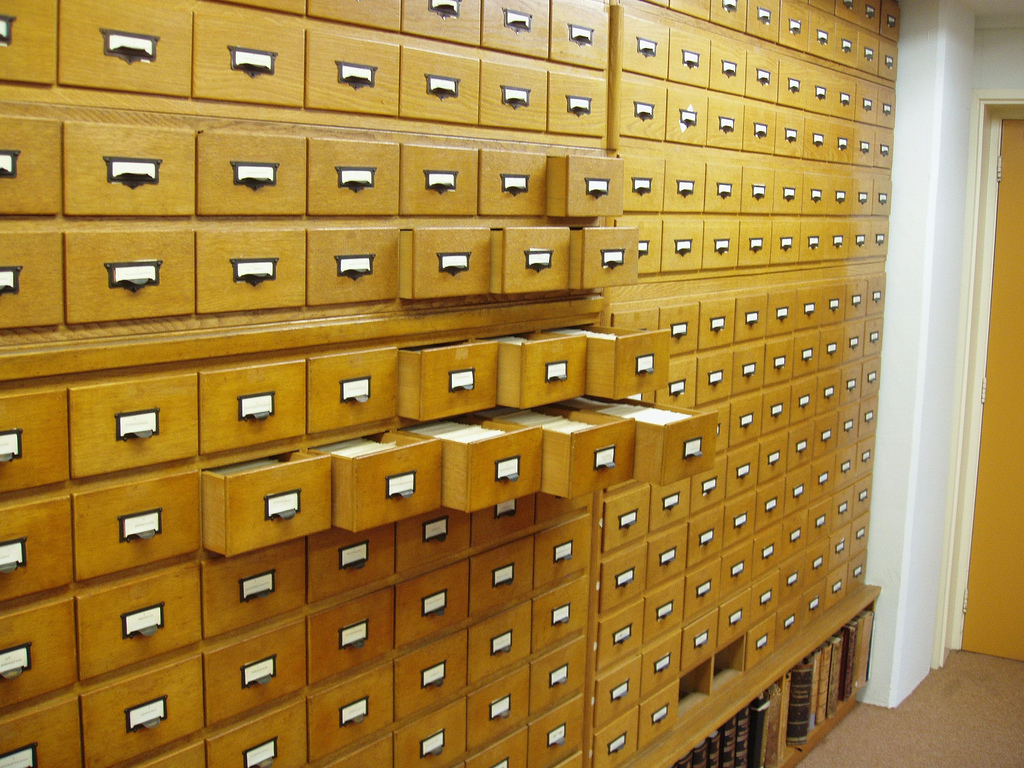

This post originally appeared in academia.edu, and was copied here in September 2014. It was revised in February 2024. The featured image is by Hindrik Sijens @ Flickr and is shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 license. The content of this post does not represent the views of the University of Thessaly or any academic entity with whom I am currently affiliated or have been affiliated in the past.

Leave a Reply